Agnes Weiyun He

September 2009

(*All photos were taken by Jackson and me during the trip.)

In the last twenty-five years we have travelled around the world. Between Jackson and myself, our journeys have taken us to about twenty countries on five continents. But we never toured our native country, except for the one-week visit to Inner Mongolia that the children and I made as part of the 2007 Summer YingHua-in-Beijing program. Then a golden opportunity came. My colleague and friend, a cultural anthropologist, Professor Greg Ruf, was taking a group of Stony Brook University students on a 26-day China Ethnicity and Ecology Study Tour in August 2009. When Greg shared with us the detailed narrative of the study tour, we were greatly intrigued and inspired. While I had concerns with health issues, Jackson felt this was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity机不可失, 时不再来 and urged that we sign up for the tour immediately.

2009 Stony Brook University China Ethnicity and Ecology Study Tour

Reed Flute Cave, Guilin 桂林芦笛岩洞

The study tour took us from Beijing 北京to Xi’an 西安, Xining 西宁, Qinghai Lake 青海湖, Chengdu成都, Lijiang 丽江, Dali 大理, Tengchong 腾冲, Wanding 畹町, Ruili 瑞丽, Kunming 昆明, Guilin 桂林 and Yangshuo 阳朔. With the exception of the flights from Chengdu to Lijiang and from Kunming to Guilin, we travelled by train and by bus and thus had an up-close view of the land and rivers in between. (We were with the study group all the time except for four days when we explored the city of Chengdu while the group went to the nearby rural area to do fieldwork.) For us, it was a dream come true. For our children Luran and Yiran, it was a thoroughly cool opportunity to travel and learn with a group of big college students and to benefit directly from the teachings of a university professor who impressed them deeply with his knowledge of and passion for those awesome places in China that mom and dad know little about. To all four of us, the study tour presented a compact and powerful course on China’s geography, history, religions, cultures, and, of course, languages.

We grew up well versed in the praise of our motherland《歌唱祖国》: “越过高山,越过平原,跨过奔腾的黄河长江;宽广美丽的土地,是我们亲爱的家乡…” Yet living in big cities like Beijing and Shanghai, we had little concrete idea what we were singing about. Our study tour took us to an astonishing array of landscapes, from the North China Plain to the loess plateau 黄土高原in Shaanxi, the grasslands of Qinghai-Tibet 青藏草原, the fertile Red Basin of Sichuan四川盆地, the Golden Summit of Emei Mountain峨眉山, the remote, rugged, and romantic Hengduan Mountains 横段山脉, the Yulong Glacier玉龙冰川 at the altitude of 4506 meters above sea level, the volcanic mountains near the border with Myanmar (Burma) 腾冲火山, the lush sub-tropical rain forest of Yunnan瑞丽莫里原始亚热带雨林, the hot springs of the Rehai geothermal field腾冲热海温泉, the Stone Forest in Kunming昆明石林, and the karst topography of Guangxi where limestone hill formations jut up from an otherwise level ground 漓江桂林阳朔.

Rape seed flowers 油菜花; Jinyintan金银滩, Qinghai Lake

Foot of Yulong Snow Mountain玉龙雪山山脚; Yulong Glacier玉龙冰川 (4506m)

Rehai geothermal field腾冲热海温泉; Stone Forest in Kunming昆明石林

We experienced our first high altitude sickness – headache, palpitations, fever, nausea, and stomach upset --when we went atop the Sun and Moon Mountain日月山 (3500m) which leads to the Silk Road and West Regions to its west and Tibet and Yunnan to its south. (It is said that this is where, during Tang Dynasty唐朝, Princess Wencheng 文成公主made up her mind to marry the Tibetan king Srongtsan Gamoi松赞干布to make long lasting peace between the Han and the Tibetan.) The sickness symptoms got worse later in the day when we stayed overnight in a yurt cottage close to Qinghai Lake at a place where 王洛宾reportedly composed the famous love song “在那遥远的地方”. After a couple of days, our bodies became acclimated, partly due to our added precaution by taking HongJingTian红景天, a Tibetan herbal medicine believed to help increase physical and mental stamina, and we had little problem when we were on top of Emei Mountain峨嵋山(3100m) in Sichuan and in the high altitude mountainous areas of Yunnan.

Sun and Moon Mountain, 日月山Qinghai; Henduan Mountains横段山脉

The train and bus rides were usually long. But we savored every moment. (It reminded us of our graduate school years when we would drive 2,000 miles in a student-budget car during one Christmas break, not toward any particular tourist destination, but just to see the land of America.) We saw Dadu River大渡河、Qingyi River青衣江、and Min River岷江that converge where the Giant Leshan Buddha 乐山大佛 is sitting. We crossed Lancang River (Mekong River) 澜沧江, which is the heart and soul of the ecosystems and the livelihoods of millions living not only in southwest China but also downstream in Myanmar (Burma), Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam. (No wonder 陈毅 wrote, “我住江之头, 君住江之尾; 彼此情无限, 共饮一江水。”) We had lunch at a rural restaurant at the end of the Nu River Bridge怒江, the site where the nationalist army fought heroic battles to deter the Japanese during WWII. On one side of the Nu River is Gaoligong 高黎贡Mountain, which, according to our local guide, in the Lisu傈僳 language, means “good fortune” (average altitude about 3500 meters). One day we were on the bus for six hours climbing over Gaoligong from Baoshan保山 to Tengchong腾冲. The road was treacherous; the view spectacular.

Lancang (Mekong) River澜沧江; Old Bridge over Nu River (旧)怒江大桥

Greg wisely took us to the First Bend of the Yangtze River长江第一湾. Pouring down from the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau are several rivers including Lancang River澜沧江, Nu River 怒江and Jinsha River金沙江. While Lancang and Nu rivers continue south, Jinsha River abruptly takes its first turn to the north as it is blocked by a huge cliff at Shigu Town 石鼓close to Lijiang 丽江, and thus forming the V-shaped First Bend on the Yangtze River. Reared by verdant mountains, Shigu Town is a historically important town on the ancient trade route for tea and horses 茶马古道between inland provinces and Tibet. It has also been a coveted locale for ambitious politicians and statesmen. During the Long March长征, Helong 贺龙 led the Red Army cross the river and went northwards to fight against the Japanese. We visited the museum and the solemn monument on top of a high slope in Shigu commemorating the Red Army. From readings after the trip, I learned that during the Three Kingdoms Period三国, the brilliant strategist of Shu State, Zhugeliang 诸葛亮, led his troop across the Jinsha River to the town. In the 13th century, Kublai Khan 忽必烈directed his Mongol troops to cross the Yangtze River right from here during his south expedition. Some suggested that it was also around the First Bend that the Great Yu 大禹 of the Xia Dynasty 夏朝 fought dauntlessly against flood disasters. 真可谓: 大江东去, 浪淘尽, 千古风流人物。All along the journey, Greg was trying to establish for us the link between the geo-environmental factors and socio-cultural practices. Indeed, if there were not a cliff at Shigu, if the Jinsha River did not turn to the north and then east, there would not have been the Yangtze River as we know it. And the trajectory of Chinese history would have taken a much different turn as well!

Shigu石鼓镇; the First Bend of Yangtze 长江第一湾

One animal species and one plant species that we encountered during the trip gave us a lot to think about: giant pandas and banyan trees. We visited The Giant Panda Breeding Research Base in Chengdu成都大熊猫繁育研究基地. We learned that pandas are endangered due to not just habitat destruction but also their extremely low birth rate. Believe it or not, pandas do not like to mate! Unlike other animals, giant pandas do not have any robust drive to procreate. Female pandas’ reproductive period only lasts several days and they ovulate once in a year. In addition, even though they have the digestive system of a carnivore, they keep a diet that is almost entirely bamboo. This means that they have to feed constantly, spending much of the time and energy that could otherwise be used on mating. It looks like this is a species that does not have a very strong desire to survive and whose innate physiology does not match its bodily practice. So, in spite of all their charm, I am having second thoughts about whether pandas should serve as a national emblem for China.

Panda Breeding Research Base, Chengdu

Panda Breeding Research Base, Chengdu

The banyan tree and its symbolism榕树. We saw many banyan trees in Yunnan. The banyan tree spreads. It has numerous aerial roots, stretching downward from nearly horizontal branches high above the ground. These roots travel about 10 feet or more downward, reach the ground and penetrate the soil. Then they thicken and form supporting pillars, indistinguishable in appearance from trunks. And from these, as well as from the upper branches, there spring fresh roots, exuberant and vital, ready to repeat the process. The tree creates an organic network where each part is different (and different sized) but supports the whole. Multiple banyan trees create a beautiful, intertwined mosaic and breathtaking scenery. Greg told us that the banyan to the rural Chinese has meant good fortune and prosperity. After the trip, I found out that there have long been rich symbolisms in India and elsewhere that are associated with the banyan tress as “the tree of knowledge” and “the tree of life”. So fitting and proper!

The banyan tree

The banyan tree

This tour certainly brought to real life and reviewed for us history lessons we have long learned from early schooling: the significance of Qin Dynasty秦朝, the terra cotta army兵马俑, the glory of Tang Dynasty唐朝, the capital city of 13 dynasties --Xi’an西安, the world’s most ingenious ancient hydraulic project Dujiang Dam 都江堰, the “way of tea” 茶道, the making of silk, among others.

The terra cotta army兵马俑; the “way of tea” 茶道

We gained lots of new knowledge as well. All our life, we have heard a great deal about the Silk Road 丝绸之路. This time, we learned more about the mysterious ancient Tea-Horse Road茶马古道, which winds and wanders across the dangerous hills and rivers of Hengduan Mountain Range, in the wild lands and forests across "the Rooftop of the World" 世界屋脊. Via this road (which passes through Tengchong, Dali, and Lijiang where we stayed), tea was carried out of mainland China to Tibet and beyond and the famous Tibetan horses were traded back into China. It is one of the world’s highest and most precipitous ancient roads which carried precious cargo and also bridged cultures. Stretching across Sichuan四川, Yunnan云南, Gansu甘肃, Qinghai青海 and Tibet西藏, it has witnessed past and present civilizations, varied ethnic customs and countless tragic or romantic stories associated with the caravan 马帮. (A September 09 entry on CND featured a true adventure of a former zhiqing 知青 who was sent to Yunnan during the Cultural Revolution and subsequently travelled with a caravan to “make revolution” in Burma which held an unusual hybrid belief of Buddhism and Marxism.)

That the Chinese civilization is not a monolithic entity is not new to us. But until this trip, we really did not have a decent knowledge beyond the Central Plain civilization中原文化. Archaeologists have long thought that Chinese civilization was born along the central plains of the Yellow River. However dramatic discoveries across China in the past 2-3 decades are challenging long-held views. We spent four days in the Chengdu plain 成都平原 in Sichuan where we had time to explore a complex and distinct ancient culture with its own artifacts and traditions—Sanxingdui culture三星堆. The (world-class!) Sanxingdui Museum is located in a small, serene city called Guanghan 广汉, not far from Chengdu. The museum displays artifacts from a previously unknown Bronze Age culture that was re-discovered in 1980s and that dated from the 12th-11th centuries BCE. Among the artifacts are bronze vessels, cups, basins, ornaments in the shape of various animals, tools, weapons, jade tables, etc., etc. The most strikingly memorable are the bronze face masks: masks with a pair of bulging eyes and a pair of fully expanded ears! They do not look like anything we have ever seen that is associated with “Chinese culture”. Our local guide in Chengdu suggested that we visit the Jinsha Ruins金沙遗址 within the city of Chengdu which indicates that civilization in southern China goes back at least 5,000 years. Unfortunately we did not have the time to do so. But this much we are now convinced of: the source of Chinese civilization is pluralistic既多元又多源; the Yellow River cannot be the sole “cradle of Chinese civilization”中华文明的摇篮. How did the miraculous bronze smelting technique and the culture symbolized by the Sanxingdui bronze masks come into being? Are they the results of ancient Shu 蜀 people's independent development or are they related to the central plains culture? Or is it the result of foreign influences, such as those from west and south Asia, or elsewhere? Why did Sanxingdui civilization disappear suddenly, leaving behind nothing in the historical record, not even in myth? “Stunned” is the best descriptor of our reaction to the visit to Sanxingdui.

三星堆Sanxingdui

三星堆Sanxingdui

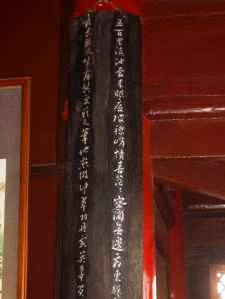

Similarly but perhaps on a smaller scale, we were very surprised and impressed by what we saw in Mu Fu, Lijiang 丽江木府—the Mu Residence. When we first heard the saying北有故宫, 南有木府(In the north, there is the Forbidden City; in the south, there is the Mu Residence), we thought it’s but an exaggeration to attract tourists. When we got there, we realized we were wrong. When Kublai Khan passed by Lijiang丽江 to conquer Dali 大理in the 13th century, the head of the Naxi 纳西people who live in this region surrendered to him. Subsequently, the governor of Lijiang submitted to the authority of the Ming Government明朝政府. The first emperor of Ming, Zhu Yuanzhang 朱元璋, granted the surname of Mu 木to the governor, and appointed him to be the magistrate 土司of this place. For about 700 years and over twenty generations, the Mus were the ruler of Lijiang. It is remarkable that though the emperors and dynasties changed as time went on, the Mus maintained a good relationship with the central government and was even constantly awarded. A very important reason is that the Mus liked to learn the culture of the Han people. They promoted “diversity” and “multiculturalism”, in today’s terminology. Under their rule, for example, the Naxi religion Dongba 东巴教and Daoism道教 complemented each other. The splendid Mu Residence (the one that has been rebuilt by the World Bank in 1990s is only half the size of the original one) combined the styles of Naxi, Tibetan and Han architectural styles. Some members of the Mus became excellent poets, calligraphists and writers of the Han language. The Mus not only successfully kept the integrity of the Naxi people, but also helped foster colorful culture and maintained long lasting peace for the region. Unlike other cities, old town Lijiang does not have any defense city walls. The tour guide told us that that is because of the surname Mu, which means “wood”—in Chinese writing, wood 木surrounded by walls 困means “captivity” or “confinement”. I suspect the openness and tolerance of the Mu family may have had something to do with it as well.

In some ways, Mu Fu is even more to my taste than the Forbidden City故宫. For one, although built in very similar styles to the Forbidden City, Mu Fu is grand but not ostentatious. Its rooftops are grey and mesh nicely into its surroundings of mountains and rivers. Its decorations are sublime but simple. For another, Mu Fu is permeated with a harmonious fusion of different cultural traditions and an astute sense of humbleness and humility. The tallest hall of the palace was not dedicated to the glory of the ruler, but rather to learning, learning literacies (Chinese, Tibetan, as well as Dongba) and religions (not merely Dongba, but also Lamaism, Buddhism, Daoism and Confucianism). Finally, this stately place manages to seem not overbearing. It has a “soft” touch that is conspicuously missing in the Forbidden City. Its courtyards are in fact reminiscent of those private citizens’ gardens in southern China.

Mu Fu, Lijiang丽江木府

This study tour also taught us new lessons in modern Chinese history. In Tengchong 腾冲and Wanding畹町, we learned more about the heroic and breathtaking adventures along the Burma Road滇缅公路 and the Stilwell Road史迪威公路 during WWII (the two roads meet in Wanding, a small town bordering China and Myanmar today).

Wanding畹町, where the Burma Road and the Stilwell Road meet.

The Cemetery of the National Heroes国殇墓园 in Tengchong has the air of the Culloden Battlefield in Scotland that we visited several years ago. It was constructed to honor the martyrs at the fierce battle recovering Tengchong from the Japanese. More than 3,000 Nationalist army soldiers and 19 American volunteers (Flying Tigers飞虎队) are buried there on a solemn, tranquil mountain slope. Chiang Kai-shek 蒋介石penned an inscription“碧血千秋”. This is an important and moving chapter of history that for presumably ideological reasons never entered the communist school textbooks that we used when we were young.

Cemetery of the National Heroes国殇墓园: Chinese soldiers and American volunteers

Heshun township和顺侨乡 in Tengchong is a mesmerizing, lyric place. It is said that more of its residents live abroad (mostly in Southeast Asia) than in town. Its pavilions, ancestral halls 宗祠, archways, covered corridors, balustrades, lotus ponds, elegant library, inscriptions, tablets and couplets all tell enchanting tales. It brought back to me memories of Brugge in the Netherlands, Avignon in France, Trier in Germany, Toledo in Spain, Sorrento in Italy… How cultures vary and yet how similar they are at the same time! Heshun is also the proud hometown of a number of noteworthy individuals in modern Chinese history, including Ai Xiqi, 艾思奇, whose residence we visited. Ai Siqi is best known for authoring 《大众哲学》 and for being Mao Zedong’s 毛泽东philosophy teacher. A legendary man from a legendary family (his father authored the famous “讨袁檄文”), Ai Siqi studied, translated, simplified, and sinified the philosophical structure of dialectical materialism辩证唯物主义. It was under his guidance and influence that Mao Zedong developed an ideological blueprint that would make Marxism applicable to China. Ai Siqi’s residence is a physical embodiment of his spirit. It is a supreme blend of the east and west sentiments. It adopts a traditional southern Chinese四合五天井 style, with an ancestral hall as well as a Victorian style balcony. The couplet outside the main hall reads: 苔痕上阶绿, 草色入廉青; the horizontal tablet: 唯吾得馨.

Heshun和顺侨乡; Ai Siqi Residence艾思奇故居

Religion was part and parcel of our learning along the way. We learned about Tibetan Buddhism藏传佛教or Lamaism in 北京雍和宫. The trip to Ta’er Si Monastery西宁塔尔寺 was meant to introduce us to the life and work of Tsong Khapa宗喀巴, founder of the Yellow Hat Sect黄教, but it was so crowded with pilgrims and tourists that day and the weather was so miserable that we could hardly hear or understand our local guide. However, we did see flickering butter lamps, smoking incense, deep chanting resonating in dim halls, and monks of all ages. This ancient religion is alive and well. I look forward to learning more about Tsong Khapa and his teachings.

Ta’er Si Monastery西宁塔尔寺

Ta’er Si Monastery西宁塔尔寺

The grandest Muslim mosque we have seen is in southern Spain, the city of Cordoba. But in Xi’an, we visited a mosque, which is surprisingly different. It does not replicate any of the features often associated with traditional mosques (round domes, etc.). Instead, it follows traditional Chinese architecture.

Chinese-style Muslim Mosque, Xi’an

Chinese-style Muslim Mosque, Xi’an

In Sichuan, we visited the Giant Buddha in Leshan乐山大佛, a statue of a Bodhisattva called Mi Le弥勒佛. Two facts about the Giant Buddha stuck in my mind. First, this gigantic project was initiated not by the imperial Tang government but by an ordinary monk called Hai Tong 海通, who was concerned with the safety of the people who earned their living around the confluence of the three rivers (Min, Qingyi and Dadu) which caused constant boat accidents. So Hai Tong decided to carve the image of the Buddha beside the river, convinced that the Buddha would stop the disasters and bless the people. And Buddha did, according to our local tour guide. After the completion of the project, accidents stopped. The local people believed Buddha answered their prayers. (The scientific explanation is probably that the tempestuous waters were eased by the fallen soil and rocks from the construction.) This was the second time we were shown that, literally, faith moves mountains. (The first time was in Meteora, Greece, where we saw monasteries built by medieval Orthodox monks on steep cliff tops.) The other impressive fact about the Giant Buddha is that this largest statue in the world has an amazing drainage system of hidden gutters and channels, scattered on the head and arms, behind the ears and in the clothes. This engineering design has helped displace rainwater and kept the inner part dry, thereby preserving the statue for more than a thousand years!

Giant Buddha in Leshan乐山大佛

Giant Buddha in Leshan乐山大佛

Our next stop from the Leshan Giant Buddha was Mount Emei峨嵋山, one of the four (and the tallest, above 3,000m) sacred mountains of Buddhism 四大佛教名山 in China. The bodhisattva being worshiped on this mountain is Puxian (Samantabhadra in Sanskrit) 普贤菩萨. Prior to the trip, Jackson’s aunt, who has a keen knowledge of Chinese culture, gave us a crash course on Buddhism in China. She told us that together with Shakyamuni 释迦牟尼 and Manjusri 文殊菩萨, Puxian forms the trinity in Buddhism. When we finally reached the peak Gold Summit (3100m), we were not just enthralled by the ten-faced, four-sided golden statue of Puxian, but also gripped by a literal sense of transcendence. As we pondered the ten different states of mind represented by the ten faces of Puxian, clouds worked their way shrouding and unveiling various parts of the mountains, presenting a visual, corporal definition of the “Pure Land” 净土. It was a very similar feeling we had at the Iguacu Falls in Brazil the year before… Nature purifies and perpetuates all souls, whichever the religion.

Mount Emei峨嵋山

On the plain north of Lijiang, we visited the Baisha Mural白沙壁画 (pictures not allowed). The mural was made about 500-600 years ago during Ming Dynasty明朝, fusing the eclectic wisdoms of Chinese Daoists, Tibetan and Naxi Buddhists and local Dongba shamans and interweaving artistic styles from previous dynasties. The result was a powerful piece of art, with rich presentations of the mystical and spiritual world full of iconographies and inscriptions that we cannot quite fully decipher. What we did understand from the visit was that during that time multiple religions co-existed side by side, calmly and complementarily. The spirit of harmonious co-existence of different religions is also evident in Tengchong, where we saw Daoist, Buddhist, and Confucius temples standing adjacent to one another on picturesque hills 儒释道三教合一.

Our knowledge of Chinese religions was broadened by our visit to Old Town Lijiang 丽江古城, the home of the Naxi 纳西people. The word “dongba” 东巴has multiple referents. It can mean the native language of the Naxi people, or their native religion, or the learned, wise men among the Naxi. Dongba the religion expresses itself not in awe-inspiring temples or distinctly observable routines or rituals, but in literacy, almost exclusively. The Scripture of Dongba Religion calls for protection and worship of every grass and tree as all living things are seen as embodiments of the gods. Before Yuan Dynasty元朝, Dongba religion had dominated the whole Naxi area. But subsequently the Naxi also accepted Lamaism from the north, Buddhism from the south, Daoism and Confucianism (as can be seen in Mu Fu). The Naxi have long been practicing what we nowadays preach: interfaith communication and collaboration.

A Daoist priest

in Mu Fu, 木府道士

A Daoist priest

in Mu Fu, 木府道士

We basked in traditional Chinese culture during this trip. We renewed our knowledge of the Chinese imperial examination system科举when we visited the Temple of Confucius孔庙 and the Imperial College 国子监 in Beijing and when we savored “cross-the-bridge rice noodles” 过桥米线 in Kunming. We saw with our own eyes ancestral halls 宗祠, archways and tablets honoring chaste and filial widows 贞洁牌坊, and the ancient drink-and-compose-poetry game board曲水流觞图. We learned about the Divine Horse art神马艺术and the making of “xuan” paper腾冲宣纸in Heshun. We were riveted by the ancient dramatic art of face-changing变脸 in Chengdu. We were reminded of the Chinese primordial emphasis on education重教兴文in Heshun, where one of the couplets reads: 高必自卑,合德智体而并育;小能见大,通天地人者为儒. (When we were young, the educational motto was “comprehensive development in morality, intellectuality, and physicality德智体全面发展”. We now know where “德智体” originated from…). We received heavy doses of poetry in杜甫草堂 in Chengdu and 大观楼in Kunming, the latter of which hosts the longest couplet (180 words) in the world 天下第一长联: 五百里滇池,奔来眼底…数千年往事,注到心头.

The ancient drink-and-compose-poetry game board曲水流觞图, Rehai热海;

The world’s longest couplet: my camera can only capture a small portion, Kunming昆明

We also had a serendipitous opportunity to visit an internationally known herbal doctor Dr. He (no relation) “神医”和士秀 in the small Naxi village of Baisha 白沙 at the foot of Yulong Snow Mountains玉龙雪山among a myriad of peasant houses. Mindful of our struggle against leukemia, Greg most thoughtfully brought to our attention this Chinese Naxi doctor who has been extensively featured in international media. In short, he is said to be able to cure the incurable. So we thought we should give it a try. As we arrived at his clinic, Dr. He stepped outside and greeted us “Hello, hello!” in English. He ushered us in and without asking our purpose of visit spent the next ten minutes or so showing us testimonials to his status and reputation --various media reports and thank-you letters from notable patients such as relatives of General Chennault and Mdm. 陈香梅, etc. When we finally had a chance to bring up the topic of leukemia, Dr. He said that he does not make diagnosis; he only provides cure. He felt Jackson’s pulse and gave two pieces of advice: (1) 保持信心 (keep faith); (2) 增强造血功能 (enhance blood-making capabilities). In order to accomplish (2), he gave us some locally grown medicinal plants in the form of powder, from a big heap that had already been sitting on his desk. He said he provides care to everyone and anyone, even if the patient is too poor to pay. We paid him what we thought was reasonable for our visit (100 RMB). As we were taking our leave, a French-speaking mother-daughter pair arrived, with something that looks like “The Lonely Planet” in their hands. And I heard Dr. He say, “Oh, this book talks about me. Yes I am famous. Many many books talk about me…” We are in no position to evaluate Dr. He’s medical expertise (we won’t take his medicine without consulting our oncologist). He may be practicing traditional Chinese medicine, but there is nothing traditionally Chinese about his demeanor.

Dr. He Shixiu “神医”和士秀; Baisha Village云南白沙

The main objective of this study tour was, in Greg’s words, to “explore the material as well as symbolic exchanges between the Han and the ethnic minority groups in China”. The tour covered five provinces (Shaanxi 陕西, Qinghai青海, Sichuan四川, Yunnan云南, Guangxi广西), home to the majority of the 55 officially recognized ethnic minorities. Greg meant and fought hard to take us to places where the minority cultures are being practiced in their natural “habitus” (a la Pierre Bourdieu). But that was by no means easy. (And certainly doing ethnography is never easy…) The local Chinese travel agencies had their ideas of what places are worthy of visit. And the local ethnic minority communities had their ideas of what about their lives should/can be shared and displayed. Nonetheless, even given the various constraints, we learned a fair amount about the Chinese Muslim汉回, the Tibetan藏, the Naxi纳西, the Dai傣, the JingPo景颇, the DeAng德昂, and the Zhuang壮. Below are a few impressions and thoughts.

Performed culture: “印象丽江”, directed by 张艺谋, Yulong Mountain玉龙雪山

Economic disparity. Our first impression was that the ethnic minority groups that we encountered on the trip appear to be living in much poorer conditions than the Han. The DeAng and the JingPo households in the model villages, for examples, looked heart-wrenchingly shabby. We have not researched the statistics. But if our impression bears any truth, a number of interrelated reasons may account for this disparity, most notably, I believe, the life styles that are resistant to change and the level of education. In preserving their traditional life styles of “slash and burn” 刀耕火种, the DeAng, for instance, are still reluctant to leave their dwellings on top of mountains and to engage in economically beneficial practices, in spite of government incentives. We were also told that few villagers in the Dai community we visited are willing to take advantage of the 12-year tuition-free education policy that is extended by the government to ethnic minorities exclusively (the general policy is 9-year compulsory, tuition-free education). There seems to be a big, substantive tension between cultural preservation and economic progress.

Inside of a DeAng household, Yunnan一个德昂人家, 云南

A DeAng 德昂lady in front of her house; a DeAng village

A Tibetan 藏民 group, Qinghai; at a Dai bungalow傣家竹楼, Ruili, Yunnan 云南瑞丽

The role of women. I don’t know how representative it is, but several minority groups characterized their culture as “men’s heaven, women’s world”男人的天堂, 女人的天下. In the case of Naxi, men are said to devote themselves to seven important undertakings in life: 琴棋书画烟酒茶(playing music instruments, playing board games, calligraphy, painting, smoking, drinking alcohol, enjoying tea), while women do all the physical work, both inside and outside the house. The hardship of the Naxi women can be seen in the sheep skin cape that they wear七星带月披肩—it has seven round embroidered discs representing seven stars, indicating that they often work from early morning before daybreak until late at night. In the Dai culture, men need to perform three years of hard labor for their prospective wife and her family before they can marry into the wife’s family. But once they become married, they enjoy the life of a king, with all the chores and labor taken care of by their women. We visited a Dai model village, where a bishao (a young married woman) told us that she was running for the office of Director of Women妇女主任, a position that is even senior to Head of the Village村长. In Kunming region where the Yi彝族live, we heard legends of Ashima阿诗玛, a clever, kind, beautiful and diligent farm girl who has become the symbol of the Yi people. Similarly, it is the story of the beautiful, brave, rebellious Sister Liu 刘三姐 that has dominated the Guilin and Yangshuo area where the Zhuang壮族 congregate. In comparison to the Han, women do appear to assume more prominent roles in these ethnic minorities.

A Naxi lady, Shigu石鼓; a group of unidentified girls, near Wanding畹町附近.

Ethnic minorities and the Han. As is the case with cultural contact, conflict and/or convergence in all other contexts, when the minorities encounter the Han culture, several scenarios take place. Some decided to gravitate toward Han by appropriating the Han language and following the Han beliefs. For example, the Naxi 纳西began the process of adaptation early (about 700-800 years ago) and voluntarily. Part of the Dai (Han Dai汉傣, as opposed to Shui Dai水傣) have assumed many aspects of the Han culture. The Zhuang壮 take the path of assimilation and today they are almost indistinguishable from the Han. Some such as JingPo 景颇and DeAng 德昂are reluctantly moving toward the Han ways of life although they would much rather keep their traditions intact. Sinicization 汉化 to various degrees and in various forms seems inevitable. Personally, I find the Naxi scenario to be the most promising-- the native culture remains robust and at the same time open to external influences.

Greg was absolutely right in pointing out at the onset that cultural assimilation is a bi-directional, mutually constitutive process: not only have the minorities been transformed through contact with the Han, the Han have been transformed through the process as well. During this trip, we met local tour guides in inter-ethnic marriages, saw houses, clothes and jewelries in assorted ethnic styles, and of course, tasted various foods prepared in interesting and sometimes incredulous ethnic manners. (My personal favorite: dumplings wrapped with bamboo shoots. Luran and Yiran’s favorite: fried grasshoppers!)

Finally, a word on maintenance of ethnic languages. Absorbed in matters related to heritage language maintenance in the U.S., I began the trip firmly believing that ethnic minority languages should be preserved, as I believe each case of language attrition is a loss of one world view. This trip has in some ways challenged my conviction. One of our local tour guides was a Naxi woman in her late 30s (who asked that I call her panjinmei 潘金妹, the Naxi equivalent of “Miss” 小姐 ). Her husband is Han and they have a daughter the same age as Yiran. So she and I had a lot to share. According to her, she never learned her ethnic language when she was in school. The government mandate to teach the Dongba language in local schools is only a recent development. Her daughter belongs to the first generation that she knows who are learning Dongba formally in school. When asked her opinion, she said that she felt her daughter is wasting too much time learning Dongba, as it is “useless”. She said that both her husband and she believe that the Han language is the only path to a bright future for their daughter. On a backstreet in the tourist center of Yangshuo 阳朔, we had dinner at a lovely restaurant that had a Chinese/English bilingual menu and served both pizza and 红烧鱼! Since we were the only dining customers at that hour, we chatted with the couple who own and manage the place. The lady was of Zhuang ethnicity. She spoke Mandarin Chinese and very impressive self-taught English, but not any Zhuang language. The reason? It’s “useless”, she said. All this makes me wonder whose purposes we will be serving if we insist on keeping ethnic languages alive when the native speakers themselves see no relevance or significance.

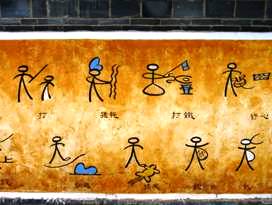

In Old Town Lijiang, we had a fortuitous meeting with a real Dongba. He was a man about our age, sitting behind a desk in a store selling stationary with Naxi insignias. We were looking around in the store and suddenly Jackson saw the sign “邂逅东巴” on his desk. We asked him, “Are you a Dongba?” He said yes, looking almost surprised that someone would be interested in his identity. We knew that in the Naxi culture Dongbas are revered for their literacy, knowledge and wisdom. So our excitement at meeting a real Dongba could hardly be contained. We talked with him for what must be a good half hour, our topics ranging from the origin and morphological characteristics of the Dongba language to the present-day commercialization of Naxi culture. Some of his statements were apparently less than accurate, but he was certainly poignant, and articulate. He claimed that scholars from forty countries are currently conducting research on the only pictographic writing system existing today but no one other than a handful of Dongbas can fully understand it. If so, I asked, why don’t the Dongbas teach the language to as many as possible? “We don’t,” he said, “we don’t even teach the language to our sons if they don’t appear to be intelligent. We only teach the really intelligent, promising boys.” Asked again why, he said it’s because literacy is the key to the Dongba religious scripture and only the intelligent ones can decipher the scripture appropriately. I made the mistake of asking him to teach me to read a line from what appears to be a Dongba language textbook on his desk. No, he said. If I really wanted to learn that sentence, I would need to spend three days sitting with him, not just a few minutes.

Dongba the language东巴文字; Dongba the wise man邂逅东巴

No doubt that this has been a very enriching and stimulating study tour. It gave ulens through which I examine and evaluate what I have seen. I may have taken the perspective of a Han, or a Chinese, or a Chinese American, or a student/scholar, or a global citizen, or maybe a combination of any or all of the above. A permanent sojourner upon the earth is perhaps what we all are, whether our life’s journeys take us to the familiar or the unknown.

Lijiang, Guangxi漓江