A Double Return: Our Trip to Ireland

Jackson and Agnes He

June 2017

For over a year now, Agnes has been suffering from an annoying (but not

life-threatening) condition called Meniere’s Disease. The vertigos, imbalances,

headaches and hearing loss have prevented her from meeting with colleagues away

from home. She has since declined all invitations to speak at conferences or to

lecture at other institutions. This month, with Jackson’s accompaniment, she

returned to her world of academic conferences for the first time – to attend the

International Symposium on Bilingualism in Limerick, Ireland. Jackson, besides

being chivalrous, was intrigued by yet another part of the world, which, for the

time being, is not under the cloud of terrorism. The prospect of driving a

manual-shift car on the left side of the road certainly added a little extra

excitement. It was the first time we combined work with leisure travel. We flew

to Dublin, drove to Limerick, spent 4 days attending the conference and touring

the vicinities of Limerick University, and drove back to Dublin where we spent 2

days sightseeing.

For over a year now, Agnes has been suffering from an annoying (but not

life-threatening) condition called Meniere’s Disease. The vertigos, imbalances,

headaches and hearing loss have prevented her from meeting with colleagues away

from home. She has since declined all invitations to speak at conferences or to

lecture at other institutions. This month, with Jackson’s accompaniment, she

returned to her world of academic conferences for the first time – to attend the

International Symposium on Bilingualism in Limerick, Ireland. Jackson, besides

being chivalrous, was intrigued by yet another part of the world, which, for the

time being, is not under the cloud of terrorism. The prospect of driving a

manual-shift car on the left side of the road certainly added a little extra

excitement. It was the first time we combined work with leisure travel. We flew

to Dublin, drove to Limerick, spent 4 days attending the conference and touring

the vicinities of Limerick University, and drove back to Dublin where we spent 2

days sightseeing.

It was also the first time in 20 years the two of us returned to global-trotting

sans children (both Luran and Yiran are occupied with their respective college

summer internships/research). The freedom of making and changing plans on the

spur of the moment brought back sweet old memories; the fun of staying in

constant touch with the children via FB messenger added new delights to our

journeys.

Landscape: the pastoral and the sublime

One way for Agnes to distract herself from the nuisances of her medical

condition in the past year is to listen to the sweet and soulful songs by the

Celtic Woman ensemble. Their lyrics portray Ireland as a land of serene beauty

and beautiful serenity:

One way for Agnes to distract herself from the nuisances of her medical

condition in the past year is to listen to the sweet and soulful songs by the

Celtic Woman ensemble. Their lyrics portray Ireland as a land of serene beauty

and beautiful serenity:

“Green the whole year ’round,

Green the whole year ’round,

The holly yew and the ivy tree

Are green the whole year ’round”

Ireland being a place to live and, often, to leave, Irish music is full of

nostalgic and longing sentiments and therefore associated with either sorrow or

soaring spirit, as evident in songs such as “Danny Boy” and “You Raise Me Up”.

BTW, music is so important to Ireland that a musical instrument – the Irish Harp

– is its national emblem!

Its landscape seems to mirror its music (or perhaps is it the other way round?). All

the travel literature we read before the trip suggests that one visits Ireland

for its nature. We (partially) agree. All the places we visited and passed by

(except for Dublin) are either humanly pastoral or widely sublime. We saw vast

fields of green, with cows, sheep, shepherds and peasants (cows just steps away

from the University Dormitory, where we stayed for the conference). Jackson

noted that there is no (and no need for) sprinkler system, as it rains ever so

often, even on sunny days. The best part of the Limerick University is the long

walks along the banks of Shannon River, under the canopy of tall trees. The

south-bank walk is at places dark, given the canopy cover, and very quiet, being

separated from the main campus by a cannel and disconnected from the main campus

near the living bridge. With swans and ducks swimming in the river, birds

chirping in the trees, and bugs buzzing in the grass, the walk feels all the

more tranquil and serene. Without any regard to us humans who happen to walk

past, life floats by as it would without us, naturally.

The Irish landscape covers the gamut from the bucolic countryside inhabited by

humans to the awe-inspiring mountains and cliffs crafted by nature, such as the

Cliffs of Moher, which is one the most visited places in Ireland, and

justifiably so. At 210 meters high, the sight is breathtaking. The “park” area

is well maintained, with stone walls to protect visitors from the cliffs. But a

few dozen steps uphill, you get to a place where you’re outside of the

controlled area, and the “park” people are not responsible for your life any

more. For a better angle to take pictures, Jackson climbed out of the protective

wall for a few minutes, against the admonition from Agnes. Because the ground is

maybe one-and-a-half to two feet above that inside the wall, stepping outside

does give you a much better vantage point for picture taking. But it also gives

you the chance to better imagine the what-ifs in life. Jackson was imagining

flying down the cliffs with a paraglider or a wingsuit. There is no safe

area to land as far as the eye can see. (And a fellow college student of his

just lost his life less than a year ago, paragliding on the west coast of the

US.) The exhibition at the visitor center is fairly interesting, with

information about the geological composition of the Cliffs, and the food is not

overpriced as is often the case at tourist traps.

The Irish landscape covers the gamut from the bucolic countryside inhabited by

humans to the awe-inspiring mountains and cliffs crafted by nature, such as the

Cliffs of Moher, which is one the most visited places in Ireland, and

justifiably so. At 210 meters high, the sight is breathtaking. The “park” area

is well maintained, with stone walls to protect visitors from the cliffs. But a

few dozen steps uphill, you get to a place where you’re outside of the

controlled area, and the “park” people are not responsible for your life any

more. For a better angle to take pictures, Jackson climbed out of the protective

wall for a few minutes, against the admonition from Agnes. Because the ground is

maybe one-and-a-half to two feet above that inside the wall, stepping outside

does give you a much better vantage point for picture taking. But it also gives

you the chance to better imagine the what-ifs in life. Jackson was imagining

flying down the cliffs with a paraglider or a wingsuit. There is no safe

area to land as far as the eye can see. (And a fellow college student of his

just lost his life less than a year ago, paragliding on the west coast of the

US.) The exhibition at the visitor center is fairly interesting, with

information about the geological composition of the Cliffs, and the food is not

overpriced as is often the case at tourist traps.

Architecture: new and old

While Agnes was attending the conference, Jackson explored the University of Limerick by himself, and gave Agnes a guided tour afterwards. We were surprised by the

rich architectural variety on campus. Almost no building is a square box, while

the vast majority has intricate yet modern designs. The connecting theme seems

to be wood or wood-like siding material. The most intriguing of the different

architectural designs is the “living bridge”, a multi-span horizontally curvy

yet vertically flat foot bridge. The bridge is a cable-suspension bridge from

the weight carrying standpoint, yet you wouldn’t know it from walking on it, as

the cables are all “inverted”, hanging from pylons that are completely below the

bridge deck, supporting the bridge above with strut-like members that rise up

from the cables. It’s really an architectural marvel, at least from an

outsider’s point of view.

Samuel Beckett Bridge. The building in the

back is the convention center.

In Dublin, the Samuel Beckett Bridge is even more innovative and evocative. It’s

a “cable-stayed bridge” with an asymmetrical design. Jackson concluded that it

looked like a harp, the national symbol of Ireland, and a web search proved that

he was right.

We visited two castles, King John’s Castle in Limerick and Bunratty Castle a

little distance off. King John is the evil king in the Robin Hood story, and is

the one who brought Ireland into British rule. The castle named after him is

kept in its ruined state, where an extensive exhibition details the Irish

history as related to the castle, and a particular battle against the castle.

This is the first time that we learned that a castle does not have to be

attacked from above ground, but can also be done from mining, and hence the word

“undermine”.

The Bunratty castle is restored in 1950s to 1960s by a private couple, Viscount

and Viscountess Gort, before being given to the Irish people. Here you get a

lecture on the operations of a castle, and a tour of a folk park that displays

uncertain-period farm life. The view from the top of the castle is spectacular,

as it is the tallest building in the surrounding area by far.

The Bunratty castle is restored in 1950s to 1960s by a private couple, Viscount

and Viscountess Gort, before being given to the Irish people. Here you get a

lecture on the operations of a castle, and a tour of a folk park that displays

uncertain-period farm life. The view from the top of the castle is spectacular,

as it is the tallest building in the surrounding area by far.

Heritage languages and heterogeneous identities

“Where is Ireland?” has an easy answer; “what is Irish?” is a much tougher

question. A lot of things said to be Irish could in fact be English and/or

Scottish. Similarly, a lot of things assumed to be English or Scottish may have

Irish origins. To make a long story short, as a result of various forces

(historical, geopolitical, economic, linguistic), today few Irish people speak

Irish (aka, Gaelic or Irish Gaelic) on a daily basis—an extremely rare situation

in Europe, where most people do speak their own native language daily. What is

the language of the Irish people’s cultural heritage? And what is its current

status? The first plenary speaker at Agnes’ conference addresses these questions

(with no clear-cut answers). To Jackson, this has more to do with National

Confidence than Identity. For, what is the official language of the US? There is

no such a thing! Although the country more or less runs on English, and from

time to time there are calls to make it the official language, nobody has tried to

call it American.

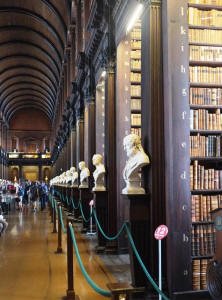

Trinity College Library.

Just as the Irish language on all public bilingual signs has now become but a

mark (not a practice) of national identity, the Book of Kells kept in Dublin’s

Trinity College is considered the finest national treasure and an enduring

symbol of Irish literary and artistic achievement. In brief, it is a book of

four Gospels in Latin, hand-copied by devout artists/calligraphers on animal

skin with extravagant illustrations and complex Christian symbolisms in a

monastery in Ireland over 1000 years ago. Like Chinese calligraphy, it is hard

to tell whether the Book of Kells is writing/text or art/painting. The pages,

paragraphs, and even individual letters of specific words are decorated with

bright-colored figures of humans, animals, mythical beasts and plants, together with

Celtic knots and interlacing patterns. We were told by the Trinity College

student guide who led the tour of the university (the library and Book of Kells

tour is not guided) that, even if we did understand Latin, the Book of Kells

would not be an easy nut to crack, as it was produced more for the illustrations

than for the texts, which can be incoherent and incorrect at places due to

various editing.

Dublin calls itself (and is endorsed by UNESCO as) “a city of literature”. It is

a relatively small city and can be covered comfortably by foot. A tour of the

Trinity College (including its library which houses the Book of Kells) requires

a fee – the only college in the world that we actually paid money to visit; a

surprise to us, as tours of all U.S. colleges and universities are free, no

matter how famous or selective.

More pictures of Dublin Writers’

Museum

are here.

A place that we happily paid money to visit was the Dublin Writers Museum. While

we were told by the student guide at Trinity College how the Irish saved the

western civilization as we know it by preserving some text and the ability to

write while mainland Europe was in the Dark Ages, this museum is not about that.

Instead, it showcases the famous writers who are Irish by birth or ancestry,

including Johnathan Swift (Gulliver’s Travels), Oscar Wilde (The Importance of

Being Earnest, The Picture of Dorian Gray), Bernard Shaw (Pygmalion, which is

the basis for the film My Fair Lady), James Joyce (Ulysses), Samuel Beckett

(Waiting for Godot) and the figures responsible for the Irish Literary Revival.

Interestingly, Wilde, Shaw and Joyce all made their name outside of Ireland, and

did not return to Ireland even after establishing fame elsewhere (in England or

continental Europe). Part of this may be due to the conservative nature of the

religion or culture. For example, at the debut of John M. Synge’s The Playboy of

the Western World there was a riot in the theater, so bad that, even when

outnumbered by policemen, the audience couldn’t be calmed. And the reason? It’s

because the audience believed that the play was not patriotic enough, and it

used a particular word that befouls the good name of Irish women. Perhaps only

in exile (whether in mind and/or in body) can one think deeply and write freely

– the Dublin Writers Museum confirmed our hunch.

Driving

Driving on the left is hard for a person used to right-side-of-road driving. Of

course Rick Steves told us “Go left, young man”, but that is not all the advice

we needed. Luckily, we had some practice previously, driving from London to

Inverness, Scotland and back. But even if you can rationalize it and understand

it, putting it into practice is a different matter. When Jackson loaded our

luggage into the trunk, he found Agnes sitting pretty in the driver’s seat,

reading a map. He asked her whether she intended to drive. “No, no, no”, she

said, “I was actually wondering why it’s so crowded in here”. The steering wheel

was somewhat in her way, of course.

And on our way from Dublin Airport to Limerick, we experienced full sun, part

sun, drizzle, rain, and heavy downpour, with a complete accompaniment of wind,

which swayed the little Corolla quite easily. Compounding our difficulties is

the flight over, which lasted more than five hours and on which Jackson watched

two-and-a-half movies. Fortunately we got to Limerick unscathed. The manual

shift, with the control rod on the left, did not give too much trouble either,

stalling the car only twice on the first day. Even roundabouts did not give

Jackson much pause. It’s the “normal” intersections with traffic lights that

brought him more mental anguish, actually.

And on our way from Dublin Airport to Limerick, we experienced full sun, part

sun, drizzle, rain, and heavy downpour, with a complete accompaniment of wind,

which swayed the little Corolla quite easily. Compounding our difficulties is

the flight over, which lasted more than five hours and on which Jackson watched

two-and-a-half movies. Fortunately we got to Limerick unscathed. The manual

shift, with the control rod on the left, did not give too much trouble either,

stalling the car only twice on the first day. Even roundabouts did not give

Jackson much pause. It’s the “normal” intersections with traffic lights that

brought him more mental anguish, actually.

On the way back from the Cliffs of Moher, both of our GPS’s pointed us down a

one-lane wide road for two way traffic, with stone walls on both sides of the

road! We decided to not follow them, and chose to take the same way back as the

one we went.

As Oscar Wilde put it, “Every portrait that is painted with feeling is a

portrait of the artist, not of the sitter.” Our travelogue surely reflects more

about what is on our mind than what is really important and impressive about

Ireland. For example, we have been remiss to not have mentioned that Ireland has

had a woman President, Mary Therese Winifred Robinson, who served from 1990 to

1997—that was 20-30 years ago! Today, Leo Varadkar, son of an Indian immigrant

and an openly gay man, is serving as its Prime Minister—cheers! And if we ever

visit this country again, we will try to learn something about its world-famous

beer, the Guiness, which, by the amount of advertisement, is half the tourist

industry in Dublin, or maybe Ireland.

For over a year now, Agnes has been suffering from an annoying (but not

life-threatening) condition called Meniere’s Disease. The vertigos, imbalances,

headaches and hearing loss have prevented her from meeting with colleagues away

from home. She has since declined all invitations to speak at conferences or to

lecture at other institutions. This month, with Jackson’s accompaniment, she

returned to her world of academic conferences for the first time – to attend the

International Symposium on Bilingualism in Limerick, Ireland. Jackson, besides

being chivalrous, was intrigued by yet another part of the world, which, for the

time being, is not under the cloud of terrorism. The prospect of driving a

manual-shift car on the left side of the road certainly added a little extra

excitement. It was the first time we combined work with leisure travel. We flew

to Dublin, drove to Limerick, spent 4 days attending the conference and touring

the vicinities of Limerick University, and drove back to Dublin where we spent 2

days sightseeing.

For over a year now, Agnes has been suffering from an annoying (but not

life-threatening) condition called Meniere’s Disease. The vertigos, imbalances,

headaches and hearing loss have prevented her from meeting with colleagues away

from home. She has since declined all invitations to speak at conferences or to

lecture at other institutions. This month, with Jackson’s accompaniment, she

returned to her world of academic conferences for the first time – to attend the

International Symposium on Bilingualism in Limerick, Ireland. Jackson, besides

being chivalrous, was intrigued by yet another part of the world, which, for the

time being, is not under the cloud of terrorism. The prospect of driving a

manual-shift car on the left side of the road certainly added a little extra

excitement. It was the first time we combined work with leisure travel. We flew

to Dublin, drove to Limerick, spent 4 days attending the conference and touring

the vicinities of Limerick University, and drove back to Dublin where we spent 2

days sightseeing. One way for Agnes to distract herself from the nuisances of her medical

condition in the past year is to listen to the sweet and soulful songs by the

Celtic Woman ensemble. Their lyrics portray Ireland as a land of serene beauty

and beautiful serenity:

One way for Agnes to distract herself from the nuisances of her medical

condition in the past year is to listen to the sweet and soulful songs by the

Celtic Woman ensemble. Their lyrics portray Ireland as a land of serene beauty

and beautiful serenity: