Mexican Matters—Our trip to Yucatan

Jackson and Agnes He

March 2009

Precursor

December 2004, the four of us entered Mexico together for the

first time, on foot. It was a short walk. The border was crowded but

peaceful. We lined up to pass the border turnstiles, the same way one

takes the subway. It appeared trivial: No one asked for our

identification. No one even paid attention.

December 2004, the four of us entered Mexico together for the

first time, on foot. It was a short walk. The border was crowded but

peaceful. We lined up to pass the border turnstiles, the same way one

takes the subway. It appeared trivial: No one asked for our

identification. No one even paid attention.

Across the border, we were greeted by the color and

commercialism of Nogales, Mexico. It seemed that the streets, big or

small, were especially created for day-tripping tourists like us. Stores

and stalls were filled with brilliant colors—of jewelry, straw hats, chinaware,

pottery, belts, shawls, accessories, etc. Shockingly, a middle-aged woman

grabbed Yiran’s arm and put a handmade bracelet on her wrist. Next to the

woman, a girl in a dirty dress raised a plate above her head with both of her

small hands, expecting payment. She looked the same height and size as Yiran,

who was then five years old. We shopped, often out of obligation, and ate,

but did nothing else. We promised ourselves that next time, we would want to see the

real Mexico.

Fast forward two years, during Christmas 2006, we embarked on our trip for the real

Mexico, and for its culture—ancient culture, to be more specific. Compared to

what we know about Chinese and Greco-Roman civilizations, our knowledge of

American civilizations was minimal. Hence we headed for the Yucatan

peninsular, the home of the Mayas. We chose Cancun because of its easy

access from New York City. We gave ourselves a crash course on the history

and culture of the region. What was awaiting us, however, was unexpected.

Travel Troubles—and Timeshare

First

of all, we had airplane troubles—due to mechanical problems, we had to transfer

in Atlanta, staying overnight, call hotel in Cancun

to change date of arrival and change car reservation online.

First

of all, we had airplane troubles—due to mechanical problems, we had to transfer

in Atlanta, staying overnight, call hotel in Cancun

to change date of arrival and change car reservation online.

Things got interesting before we exited the Cancun airport. To

get to our hotel, we needed a taxi. We were told to book one at an info booth.

There was a whole array of booths lined up, and there was no telling how they

differ from each other. We stopped by the first booth, where the person gave us

some ambivalent info, and then tried to get us to a place where we could get

“free breakfast.” The only thing was, we had to put down $100 US first, to be

returned at the breakfast. We had just run into our first Mexican timeshare

agent! We declined, and paid only for a taxi, as we originally planned.

Outside the airport terminal, we waited for a long time and

couldn’t get a taxi. When we complained, “no problem!” an agent said, “you can

take a van.” But we paid for the higher fare for a taxi! “No problem,” he

assured us, the van can go to our hotel first. The usual route for vans is to go

through the hotel zone, a huge and isolated international area that is mostly

devoid of local Mexicans. Our hotel was in downtown, which is at the end of the

usual van route.

One major difference between hotels in downtown Cancun and

the hotel zone is the extra distance to the beach. Cancun is famous for its

white sand beach, where the sand is supposedly made of granulated seashells, and

is cool to the feet. Hotel zone is situated on a long and curvy beach road. But

our hotel boasts of a free shuttle to the beach, where it has a part ownership

in a beach club. That was the advertisement that got us there. Upon arrival,

however, we were told that the shuttle was not running, because the beach club

was closed. The concierge was very ready to help us make it up, by providing a

free taxi to the Royal Sands Hotel, where we could enjoy the beach whole day, a

free breakfast, and, you guessed it, a timeshare presentation! Not willing to

give up the beach completely, we bit this time. It is hard to say no to a

timeshare salesperson, and it is even harder to have the answer accepted, but it

is not impossible—we lived to prove it!

One major difference between hotels in downtown Cancun and

the hotel zone is the extra distance to the beach. Cancun is famous for its

white sand beach, where the sand is supposedly made of granulated seashells, and

is cool to the feet. Hotel zone is situated on a long and curvy beach road. But

our hotel boasts of a free shuttle to the beach, where it has a part ownership

in a beach club. That was the advertisement that got us there. Upon arrival,

however, we were told that the shuttle was not running, because the beach club

was closed. The concierge was very ready to help us make it up, by providing a

free taxi to the Royal Sands Hotel, where we could enjoy the beach whole day, a

free breakfast, and, you guessed it, a timeshare presentation! Not willing to

give up the beach completely, we bit this time. It is hard to say no to a

timeshare salesperson, and it is even harder to have the answer accepted, but it

is not impossible—we lived to prove it!

We reserved a car at Hertz downtown before our trip. When we

got to the place, we were told there was no car. “But what about our

reservation?” Jackson protested. “The person (previous renter) should have

returned the car,” he was told. At our hotel, we also have a travel agent (who

also happened to be a timeshare agent), who could rent us a car any time, only

at twice the price of our Hertz reservation. Maybe it was all for the better

that we did not rent a car in Mexico, since if there was an accident, we’d be

assumed guilty until proven innocent. And with our next to nil Spanish, we would

not be in a good position to prove anything.

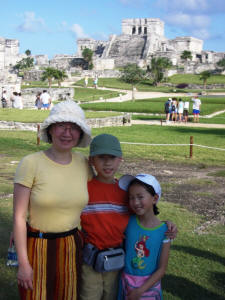

Tulum, a fortress in ruins.

We ended up traveling as locals do some of the time, such as

taking a long distance bus from Cancun to Tulum. For this our hotel’s downtown

location gave us a distinct advantage: the bus terminal, as well as a super market, is well within walking distance. Not

knowing the setup of things, we bought our tickets on a smaller bus line, which

made more frequent stops. A bigger bus line, by the name Ado, seemed to be going

faster and have the bigger and more comfortable equipment. On the bus, we talked

with a young woman on her way to Playa del Carman, and found out that her

parents own a timeshare where she boarded the bus.

For our visit to Chichen Itza, we took a tour bus from the

hotel zone. This is a service tailored to the “rich” foreigners. It started off

with a “registration” step conducted deep inside a large, two-story souvenir

store. On the way to Chichen, the bus took us to a “Mayan village”, which turned

out to be a huge, over-priced tourist gift shop, for which our tour guides made

compassionate plugs ahead of time. We took the bait, bought souvenirs

high-priced (a silver pendant with Mayan hieroglyphic) and low-priced (a Mayan

calendar painted on leather) alike. But our tour guides also warned us of the

“Mayan dollar” sales scheme used rampantly on the Chichen Itza grounds—some

handiworks vendors would shout “one dollar, one Mayan dollar” to get people’s

attention; but since there is not such a thing as a Mayan dollar, this is just a

gimmick to get the bargaining started.

In Mercado 28 (a local market place), we consulted with a

travel agent about a trip to Xcaret, a Mayan theme park. We were told the price

would be $150 US per person. “Too expensive,” we complained. No problem,

the travel agent replied. He could sell us the tour package for $50 US per

person, if we could sit through a—guess quickly—timeshare presentation! When we

declined, he reduced the price to 0, plus free food (not only at the timeshare

place, but at Xcaret as well)—all paid for by the requisite timeshare

presentation!!!

In Mercado 28 (a local market place), we consulted with a

travel agent about a trip to Xcaret, a Mayan theme park. We were told the price

would be $150 US per person. “Too expensive,” we complained. No problem,

the travel agent replied. He could sell us the tour package for $50 US per

person, if we could sit through a—guess quickly—timeshare presentation! When we

declined, he reduced the price to 0, plus free food (not only at the timeshare

place, but at Xcaret as well)—all paid for by the requisite timeshare

presentation!!!

In spite of our inability to escape from commercialism, we

took relief in the fact that we did not stay in the hotel zone. By

choosing a hotel in downtown, we got to meet some local people in their natural

habitat—supermarkets, bus terminals, local restaurants, the market place, and a

local church, the service of which we attended on Christmas Day. It is

hard for us to appreciate the concept of a hotel zone, which is physically

adjacent to the remnants of an ancient culture and yet feels so out of place.

Sites and Sights

The pyramid at Chichen Itza supposedly encodes Mayan calendar, which is

said to end in year 2012.

Chichin Itza is the most famous in the area, and is quite

crowded. It was very hot on the day we went. It’s also a place that is hard to

get to—there seems to be hardly anyone living on the way from Cancun, or

anywhere else for that matter. It is hard to believe that when the pyramid was

built a few hundred years ago, there were more than a million people living in

the surrounding area. For those few who live there now, life seemed to be quite

hard. By showing us how poor the local residents really are, our tour guides

successfully programmed our minds for generous purchases at a local market place

set up expressly for (mainly foreign) tourists.

The pyramid of Chichen is of moderate size when compared to

other large-scale manmade structures in the history. But when put in such a flat

area with almost no arable land, it’s quite remarkable. Our guide blamed the

human sacrifices of the yesteryear on the Toltecs, who came to the region,

conquered and intermingled with the Mayans. He exulted in the achievement

reached by the pyramid in Chichen Itza, which supposedly represented the Mayan

understanding of the calendar, with just the right number of steps to represent

the number of days in a year, etc. Interpreting the pyramid as a Mayan calendar

is intriguing, but unfortunately it does not account for the other pyramids in

the region, such as the one in Tulum.

Playa del Carman is a famous playground, where locals as well

as visitors tend to congregate. A ferry boat sails regularly between the Playa

(which literally means beach) to Cozumel, another, albeit slightly less famed,

international tourist destination. We spent some time on the beach, and found

the beach sand to be less smooth compared to that at the beaches in Cancun. On

the other hand, the shopping streets were much livelier, full of small shops

selling local trinkets, etc. We spent a nice evening sitting on the balcony of a

restaurant, enjoying fine food and a fancy street scene, concurrently.

Xcaret is sometimes despised as the Mayan Disney. But we were

not put off by that characterization—we’ve been to Disneyland (before children)

and Disney World (with children), and enjoyed both experiences. As it turned

out, we enjoyed Xcaret quite well. It’s at this place that we got to experience

snorkeling, where colorful tropical fish all of a sudden show up right in your

face when you enter the water. The Mayan culture show at night is rather

interesting, although not as polished as any Disney show. Part of the show had

two teams playing with a fire ball, which was quite captivating, especially to

kids. The show was conducted in Spanish, so we were not the main target

audience.

Xcaret is sometimes despised as the Mayan Disney. But we were

not put off by that characterization—we’ve been to Disneyland (before children)

and Disney World (with children), and enjoyed both experiences. As it turned

out, we enjoyed Xcaret quite well. It’s at this place that we got to experience

snorkeling, where colorful tropical fish all of a sudden show up right in your

face when you enter the water. The Mayan culture show at night is rather

interesting, although not as polished as any Disney show. Part of the show had

two teams playing with a fire ball, which was quite captivating, especially to

kids. The show was conducted in Spanish, so we were not the main target

audience.

The Mayan relics are in a great state of ruins. This is at

least partly due to the nature of the material they used. The rocks in the

region are quite soluble, such that holes are naturally made by water running in

them, to allow all rivers in the region to flow completely underground, and for

a kind of natural well, called cenote, to be formed. The cenotes

provide the locals drinking water, and are also the locations for some of the

human sacrifices. A recent report indicates that remains of hundreds of people

were found in a cenote at Chichen Itza, including those of adults as well as

children.

Another reason for the extremely dilapidated state of Mayan

artifacts is their lack of metallic tools. Spaniards found the Mayans in the

Neolithic period of human development. Compared to the refined stone sculptures

of Greek and Roman classical periods, the Mayan carvings likely suffered from a

lack of finesse from the very beginning. And as far as we know, they’ve never

made free-standing sculpture, statutes of live sizes or beyond, statutes with

idealized human or animal shapes or postures, or ones with vivid emotions.

We spent part of our Christmas day in a church. Spanish Conquistadors forcefully

converted the locals including Mayans to Catholicism, which is practiced widely

even today.

What made matters much worse was that when the conquistadors

arrived in the 16th century, they brutally subjugated the locals.

Their comprehensive carnage of the local culture included the burning of all the

books in Mayan language (only a precious few remain today), and the abolishing

of Mayan written language. It was only in the last few decades that the Mayan

written language was deciphered, and taught to the Mayans again. For a

culture to have lost its language is for a person to have lost her soul…

Our trip reminded us that we are privileged to have been born and socialized in countries with long and rich heritages. The Asian and European

civilizations have learned to work with bronze, iron and steel for a few millenniums,

have long recorded histories, and have left us with archeological and cultural

artifacts that continue to stun and stimulate us. We indeed ought to be proud

of our cultural lineage. But in the time frame of millions of years of natural

evolution, or even within the hundreds of thousands of years of homo sapiens’

existence, a couple of thousand years only amounts to a blink of an eye. In a

larger cosmic context, we are not that much different from our ancestors of a

few thousand years ago, were we not gifted with the cumulative knowledge of the

civilizations in between. And that knowledge, whether originated from our own

ancestors or someone else’s, really belongs to humanity as a whole. Earth

is but a small lifeboat for us all.

December 2004, the four of us entered Mexico together for the

first time, on foot. It was a short walk. The border was crowded but

peaceful. We lined up to pass the border turnstiles, the same way one

takes the subway. It appeared trivial: No one asked for our

identification. No one even paid attention.

December 2004, the four of us entered Mexico together for the

first time, on foot. It was a short walk. The border was crowded but

peaceful. We lined up to pass the border turnstiles, the same way one

takes the subway. It appeared trivial: No one asked for our

identification. No one even paid attention.

In Mercado 28 (a local market place), we consulted with a

travel agent about a trip to Xcaret, a Mayan theme park. We were told the price

would be $150 US per person. “Too expensive,” we complained. No problem,

the travel agent replied. He could sell us the tour package for $50 US per

person, if we could sit through a—guess quickly—timeshare presentation! When we

declined, he reduced the price to 0, plus free food (not only at the timeshare

place, but at Xcaret as well)—all paid for by the requisite timeshare

presentation!!!

In Mercado 28 (a local market place), we consulted with a

travel agent about a trip to Xcaret, a Mayan theme park. We were told the price

would be $150 US per person. “Too expensive,” we complained. No problem,

the travel agent replied. He could sell us the tour package for $50 US per

person, if we could sit through a—guess quickly—timeshare presentation! When we

declined, he reduced the price to 0, plus free food (not only at the timeshare

place, but at Xcaret as well)—all paid for by the requisite timeshare

presentation!!!