Krakow main square.

Jackson and Agnes He

November 2017

Poland is unlike any other European country we had visited before. First, geographically, it is located in Central Europe. Second, given its history, it lures us with a blend of strength, softness and subtlety.

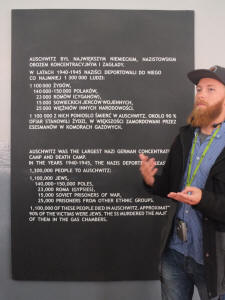

In September 2017, we visited two cities in Poland, Poznan and Krakow, and the Auschwitz concentration camp near Krakow. Poznan has few international visitors. Krakow has many. Auschwitz is filled with them.

Our first impression was that Poland seems Lake Wobegon come true—where all the women are strong (and striking!), all the men are good-looking! Poles, men and women alike, appear elegant and energetic. Our second impression was that the Polish population looks extraordinarily homogeneous. Our third impression was that, in spite of its apparent ethnic homogeneity, the Poles are very worldly and very friendly. No one seemed to pay attention to our obvious differences and everyone was very willing to help whenever we asked for it.

Using audio tours Jackson downloaded prior to our trip as our guides,

we toured much of Poznan and Krakow by ourselves. We learned the cities’

histories in relation to the landmarks. We learned of Poland’s early history,

its connection with Lithuania that led to a Commonwealth, its partitions by

Russia, Prussia and Austria, when Poznan was annexed by Prussia and Krakow by

Austria. We saw statues of Adam Mickiewicz in both Poznan and Krakow, and Agnes

attended a conference at a university named after him. Mickiewicz was a famous

poet, and poems by him and others established the “Polish Romanticism” movement

when Poland as a country was no more in existence. We saw the balcony at Hotel Bazar where pianist and composer Ignacy Paderewski made his firing speech

calling for the uprising of Poznan. It’s because of people like Mickiewicz and

Paderewski that an independent Poland was reborn after 123 years. Sadly, Poland was invaded by

Hitler and Stalin during the early stage of WWII, and the infamous Auschwitz

Concentration Camp was built by Nazis near the Polish town of Oświęcim. After

the war, with the Red Army in control of both Poland and eastern Germany, Stalin

obtained Churchill and Truman’s consent to his plan for the restoration of

Poland, carving out a large area in its east to give to the Soviet Union, and taking

a smaller area in the west from Germany.

We also learned about another linkage in Polish-US relationship. A prominent Pole, by the name of Tadeusz Kościuszko, was no less than a hero in the American Revolution! Much is known about his military contribution. But what impressed us the most is his firm belief in liberty and justice for all, including persons of color, as evident in his American will. Before Kościuszko left the U.S., he wrote a will, and entrusted it to Thomas Jefferson as executor. (Kościuszko and Jefferson were firm friends for many years in a spirit of mutual admiration. Jefferson wrote that “He is as pure a son of liberty as I have ever known.”) In the will, Kościuszko left his American estate to be sold to buy the freedom of black slaves, including Jefferson’s own, and to educate them for independent life and work. Kościuszko’s American will was never carried out due to various reasons; it would take the Americans another 80+ years to end black slavery.

We enjoyed the medieval town squares in Poznan and Krakow. We visited Royal Apartments in the Wawel Castle. And along the way, we passed by many, many churches from various historical periods.

The trip also took us to people and places we already “know”.

L. L. Zamenhof is the creator of Esperanto (known as an ‘international language’;

but literally, ‘Esperanto’ means the language of ‘hope’). Zamenhof was born in

the mid 19th century to a Jewish family in the part of Poland under Russian

rule, where the population consisted of Poles, Jews, Germans and Russians and

where the tensions and suspicions between different ethnic and linguistic groups

were evident. Drawing upon his own linguistic repertoire (Russian, Yiddish and

Polish, and then German, Hebrew, Latin, French, English, Greek and some

Lithuanian, Spanish and Italian), he created Esperanto in the belief that a

common language would enable different groups to come together and to dissolve

the entrenched hatreds between them. The goal is lofty and idealistic,

and the supposedly ‘international’ language is largely Indo-European-centric.

Nonetheless, it was probably the greatest effort made in human history to

construct a human language to benefit more than one single nation or one single

ethnic group. The conference (International Interlinguistic Symposium) where

Agnes gave a paper on intercultural linguistic repertoire at the Adam Mickiewicz

University in Poznan commemorated Zamenhof’s work.

L. L. Zamenhof is the creator of Esperanto (known as an ‘international language’;

but literally, ‘Esperanto’ means the language of ‘hope’). Zamenhof was born in

the mid 19th century to a Jewish family in the part of Poland under Russian

rule, where the population consisted of Poles, Jews, Germans and Russians and

where the tensions and suspicions between different ethnic and linguistic groups

were evident. Drawing upon his own linguistic repertoire (Russian, Yiddish and

Polish, and then German, Hebrew, Latin, French, English, Greek and some

Lithuanian, Spanish and Italian), he created Esperanto in the belief that a

common language would enable different groups to come together and to dissolve

the entrenched hatreds between them. The goal is lofty and idealistic,

and the supposedly ‘international’ language is largely Indo-European-centric.

Nonetheless, it was probably the greatest effort made in human history to

construct a human language to benefit more than one single nation or one single

ethnic group. The conference (International Interlinguistic Symposium) where

Agnes gave a paper on intercultural linguistic repertoire at the Adam Mickiewicz

University in Poznan commemorated Zamenhof’s work.

Copernicus (Mikolaj Kopernik in Polish) formally challenged Ptolemy’s

earth-based solar system theory, which was adamantly supported by the

influential Roman Catholic Church. Even though Copernicus was not the first one

to conceptualize a heliocentric solar system, in which the sun, rather than the

earth, is the center of the solar system, his heliocentric system proved to be

more detailed and accurate than others before him, with a more efficient formula

for calculating planetary positions. And even though his theory is not accurate

(he assumed, for example, planetary orbits are perfect circles),

Copernicus has become a symbol of the bravery of scientists in face of

oppression and irrationality. In the magnificent Collegium Maius in Krakow (of The Jagiellonian

University, founded in 1364, the oldest university in Poland), there is a

special exhibition room dedicated to Copernicus. On top of the frame of the door

leading to the room is the University’s motto: Plus Ratio Quam Vis (let reason

be greater than force). Copernicus studied at Jagiellonian University and majored in Philosophy. We saw his name (along with that of his brother) listed on

the University tuitions and fees roster dated 1492. We also saw the astronomical

instrument he might have seen and used during his time.

Copernicus (Mikolaj Kopernik in Polish) formally challenged Ptolemy’s

earth-based solar system theory, which was adamantly supported by the

influential Roman Catholic Church. Even though Copernicus was not the first one

to conceptualize a heliocentric solar system, in which the sun, rather than the

earth, is the center of the solar system, his heliocentric system proved to be

more detailed and accurate than others before him, with a more efficient formula

for calculating planetary positions. And even though his theory is not accurate

(he assumed, for example, planetary orbits are perfect circles),

Copernicus has become a symbol of the bravery of scientists in face of

oppression and irrationality. In the magnificent Collegium Maius in Krakow (of The Jagiellonian

University, founded in 1364, the oldest university in Poland), there is a

special exhibition room dedicated to Copernicus. On top of the frame of the door

leading to the room is the University’s motto: Plus Ratio Quam Vis (let reason

be greater than force). Copernicus studied at Jagiellonian University and majored in Philosophy. We saw his name (along with that of his brother) listed on

the University tuitions and fees roster dated 1492. We also saw the astronomical

instrument he might have seen and used during his time.

Pope John Paul II (Karol Józef Wojtyla) was the first non-Italian Pope in more

than 400 years and the first Pope who touched our hearts with his advocacy for

human rights, compassion for all who suffer, respect for other religious

persuasions, and his association with the fall of communism in his native Poland

and then the entire Europe. He was an alum of Jagiellonian University and was

the archbishop of Krakow in 1960s. Naturally, he is the pride and treasure of

not only Krakow but the entire Poland. We saw a full figure statue of him near the

Poznan bishop’s residence, a bust of him in the Medical College in

Krakow, a portrait of him in Collegium Maius, a statue of him in the courtyard

of the Wawel Castle, as well as a large banner bearing his image at the monastery where he lived for many years in

Krakow.

And of course there is the great romantic composer and pianist Frédéric Chopin,

the pride and idol of Poles of all nations. It is

said that even though he spent most of his time in France (and even though his

father was French), Chopin never became fluent in the French language, preferring to

speak Polish instead and remained at heart an ardent Polish patriot. His French

citizenship was merely an effort to avoid dealing with Imperial Russian

bureaucracy.

Chopin was physically frail, intellectually brilliant, and

emotionally often torn by love, language, and identity – in a way emblematic of

his native country to which he never returned. Like many geniuses, he died

young, at the age of 39. A plaster cast of his left hand was on display in Collegium Maius.

Music boxes with Chopin’s melodies filled the shelves in souvenir stores. Music

permeates the two Polish cities that we

visited; we wished we had had the energy to attend the various performances held

in churches and concert halls. Fortunately we have at home a complete

CD set of Chopin, a birthday gift for Jackson from a dear Polish friend of ours.

The city Krakow occupies a special place in Agnes’ heart. Many years ago, Agnes read a linguistic memoir “Lost in Translation: a Life in a New Language” by Eva Hoffman, a Polish-American writer who left Krakow for North America at the age of 13. That book strikes a deep chord. As Hoffman put it, the city of Krakow is “a place of not of mystery but of secrets, a city of shimmering light and shadow with the shadow only adding more brilliance to the patches of wind and sun.… its narrow byways, its echoing courtyards, its jewellike interiors … cave-like cafes with marble-topped tables, medieval church spires, and low, Baroque arcades…” The city landscape Hoffman portrays in the book remains the same. Krakow escaped the destruction of WWII. It looks like it has always existed and always will, for the nostalgic and the adventurous alike. We came upon the Krakow Academy of Music but are not sure whether it is the same music school that Hoffman attended.

Agnes put Auschwitz on the top of our must-see list for Krakow. She has deeply-rooted reasons for that decision. Whether by choice or by chance, many of the individuals who have played a profound role in shaping her career-paths and world-views have been Jews – professors, fellow students, colleagues, mentors, writers. Furthermore, many of the families that we have looked up to for example as we tried to identify and create opportunities for our children during their formative years are Jewish American families as well. Hence visiting Auschwitz was, in an oblique way, for her/us to pay respect to the history of the people who are dear to her/our heart.

It requires much emotional fortitude to visit Auschwitz. We had long learned of the holocaust, of the scale of the massacre, of the method, and even of the entrance gate marked with the slogan “Arbeit macht frei” (work sets you free). We had read Anne Frank (and visited her house in Amsterdam) and Elie Wiesel. We had watched “Schindler’s List”. But to brave it all, and to be shown the depth of human bestiality where it happened, was an emotional ordeal at a completely different level.

Picking us up from a designated spot close to our AirBNB apartment was Conrad, a polite and

professional young man with a degree in Western History from the Jagiellonian

University (Poland’s oldest university, located in Krakow) and an impeccable

command of English. He drove a small van that can sit about eight. We were his

first passengers, and we made two more stops in Krakow to pick up the rest. It

turned out that Conrad was going to be our guide for the day as well.

Picking us up from a designated spot close to our AirBNB apartment was Conrad, a polite and

professional young man with a degree in Western History from the Jagiellonian

University (Poland’s oldest university, located in Krakow) and an impeccable

command of English. He drove a small van that can sit about eight. We were his

first passengers, and we made two more stops in Krakow to pick up the rest. It

turned out that Conrad was going to be our guide for the day as well.

When we arrived at Auschwitz, we met the other people of our guided tour. They came from the UK, probably as a part of a big tour package, as opposed to the few of us who came with Conrad as a daytrip from Krakow. Now we had a group of about 30 in total. Fortunately, for Auschwitz I, which is run as a museum, we each got a radio receiver dialed into Conrad’s channel, and as such we could hear him clearly without having to stay close to him, and he did not have to raise his voice in order to be heard. This surely helped. His voice was subdued, due to the grave nature of the topic, and the place, even with hundreds of visitors, was hushed. This is where tens of thousands of people were murdered.

We saw stats. We saw pictures, of the camp, the people, and the running of the

camp. We saw where people were housed (crammed), treated medically (not for cure

but for medical experiments), and imprisoned (this even inside a concentration

camp!), and tortured and killed, either in small groups, or en masse in a gas

chamber. We saw piles and piles of shoes, glasses, and suitcases left by the

victims, but the most heart-wrenching sight was the pile of human hair. When the

Red Army liberated Auschwitz, they found seven tons of human hair. Apparently

they were shaved from people who had just been gassed to death. For the purpose

of making some kind of cloth! Absolutely abhorrent – people don’t even kill the

sheep in order to harvest their wool! Then we realized that we were totally wrong.

Nazis didn’t kill for financial gain; that was only a byproduct. Killing was the

goal. It was the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question”.

We saw stats. We saw pictures, of the camp, the people, and the running of the

camp. We saw where people were housed (crammed), treated medically (not for cure

but for medical experiments), and imprisoned (this even inside a concentration

camp!), and tortured and killed, either in small groups, or en masse in a gas

chamber. We saw piles and piles of shoes, glasses, and suitcases left by the

victims, but the most heart-wrenching sight was the pile of human hair. When the

Red Army liberated Auschwitz, they found seven tons of human hair. Apparently

they were shaved from people who had just been gassed to death. For the purpose

of making some kind of cloth! Absolutely abhorrent – people don’t even kill the

sheep in order to harvest their wool! Then we realized that we were totally wrong.

Nazis didn’t kill for financial gain; that was only a byproduct. Killing was the

goal. It was the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question”.

The museum tour at Auschwitz took about an hour and a half. After a quick break, we rode the vans to Auschwitz II-Birkenau. We could use the time to grab a bite, but Conrad apparently didn’t eat anything, and Jackson decided to abstain as well.

The Auschwitz II-Birkenau concentration camp is massive. And in this part of the tour we didn’t have radio communications any more. Unfortunately due to the sheer size of the place we were often stragglers of the group, due to Agnes’ health condition, and struggled much to try to catch up with the group.

Auschwitz II-Birkenau is a place purposefully designed to kill people in larger

quantities and with greater efficiency. People fresh off the trains were sorted

by the SS, and the children, the women, the old, and the sick, were marched to

the end of the rail line, where they were gassed in large

gas chambers, up to 15,000 people a day. It’s truly unfathomable that humans were

capable of committing repeated mass murders, economically and methodically, day in and day out. And not for what the victims did, but for what they were.

Jews. Gypsies. Homosexuals. Jehovah’s witnesses.

Auschwitz II-Birkenau is a place purposefully designed to kill people in larger

quantities and with greater efficiency. People fresh off the trains were sorted

by the SS, and the children, the women, the old, and the sick, were marched to

the end of the rail line, where they were gassed in large

gas chambers, up to 15,000 people a day. It’s truly unfathomable that humans were

capable of committing repeated mass murders, economically and methodically, day in and day out. And not for what the victims did, but for what they were.

Jews. Gypsies. Homosexuals. Jehovah’s witnesses.

How can some human beings be so diabolic? How can we tell that some living among us are not just like them, waiting for the right moment to jump out and do the evil deeds? How can we be sure that enough people have learned this lesson, and will come forward to stop the next Hitler? It sends chills down to the spine to realize that we do not have clear answers to any of these questions.

Due to some track repair work, trains between Berlin and Poznan were not running from end to end. Consequently we took three long distance buses while traveling to, from and in Poland, two of which were overnight trips.

The bus stations in Poland (Dworzec PKS) are in much better condition than the central bus station in Berlin (ZOB). Polski buses are very punctual also, sometimes to the minute. We were a bit worried in Poznan, until ten minutes before our departure time, when the bus showed up. But unfortunately sometimes services are somewhat lacking. We found out while in Poznan that the bus station clerks all get off work in early evening, even though the buses come and go throughout the night. Signs are not always translated into English (or any other language) either. Were it not for the experience in Poznan, we could have missed our Krakow to Berlin bus, as the departure time was again in the evening, when the travelers were abandoned to help themselves, but our bus from Krakow to Berlin was indicated on the display board as going only to Wrocław!

While Eva Hoffman’s book focuses on disorientation in the figurative sense, we,

for a few times, felt quite lost physically in Poland.

It is not easy for us to travel in Poland, as we do not speak any Polish at all. On the day of our arrival, at the door of Adam Mickiewicz University’s Collegium Novum (new college), Agnes asked a young and beautiful girl where she can find the statue of Adam Mickiewicz. The girl replied in flawless English that the university was named after a poet, the most famous poet of Poland, and that the university was the best in Poland!

On the next day Jackson went to the National Gallery in Poznan. Finding no one at the front desk, he asked a woman in the vicinity: “Do you speak English?” She replied: “No.” He said: “Is the museum free?” She said: “No.” He spread his hands, and shrugged, what was he to do? She pointed behind him, where another lady was approaching. This was the ticket agent. This lady did not speak English either. But when he asked her in English: “credit card?” she said “No”. Not wanting to be presumptuous, he took his camera out of the bag that was to be checked, and asked simply: “Camera?” The lady said: “No flash!”

In the museum, while he was debating where to go first, a woman came to his rescue. She pointed to the plan in his hand. There was a map, he nodded. He was just trying to comprehend the lay of the land. She then pointed to somewhere on the wall. He nodded again. The same color-coding scheme on the wall as in the plan made things transparent. She introduced him to a different lady in Polish, and the person passed him on to the next one, etc., and after several relays, he was led to the European art section on the third floor (floor 0 being the street level)! Did he go all the way to Poland, to see the European art? 80% of the museum’s exhibition is Polish art! It turned out when she pointed to the plan and the directions on the wall, she pointed to a specific section, while Jackson took it to mean the overall directory. Fortunately, this was as far as he could go, and with no more help coming his way, he was able to slowly work his way to the three sections of Polish art!

Eating where the locals do was also a challenge. Agnes saw a restaurant where the food pictured looked delicious, and we decided to eat there. But we couldn’t read the menu. So she pointed to a dish someone else just ordered. Jackson told Agnes that he didn’t like the fact that the meat was fried. A lady in the queue heard us, and quietly translated his words to the lady behind the counter. Not a problem! Out came a dish of large meat balls, with boiled potatoes and pickled cabbage, all of which were very delicious! After the meal, Jackson found that the restaurant had a copy of the menu in English. It turned out the restaurant is like a cafeteria, with different menu items for different days of the week. Next day Jackson went back again, and found the same lady behind the counter. With a smile instead of words, he ordered the dish that was not fried, this time being stewed pork tenderloin, also very delicious, and inexpensive, less than US$5, including a bottle of water.

We of course benefited greatly from many Poles who speak the kind of English we are familiar with. Other than Conrad, our guide to Auschwitz, the young lady who guided our tour of Collegium Maius (it was a scheduled English tour with only the two of us as tourists) was superb as well. It is a pity that we did not have enough time to get acclimated to Polish-style-English; otherwise we could have understood our Wawel tour guide much better. Right under Wawel, we went to a Michelin-rated restaurant, Pod Baranem (meaning Under the Ram Head), which has great Polish food, and which was recommended to us by our AirBNB host. We found the paintings on the wall to be somewhat unsettling, even disturbing, to the degree that we asked that our room be switched. When Agnes inquired about these paintings, the waiter brought out an art book about the artist, Edward Dwurnik. We learned that he was the first Polish artist who deviated from the classical fine art, and depicted ordinary people and everyday lives with all of their imperfections, thematically and stylistically. The restaurant’s entire interior is fully decorated with his work.

We

didn’t plan to go to Berlin, per se. But the venue of Agnes’ conference,

Poznan, Poland, lies in the middle of Berlin and Warsaw. Having been to neither

city, we were attracted by Berlin’s magnetic historical and symbolic

significance, especially in regard to WWII and the Cold War. Most people know no

German, yet many know JFK’s famous words: “Ich bin ein Berliner!”

said in Berlin, during the early days of the Cold War.

We

didn’t plan to go to Berlin, per se. But the venue of Agnes’ conference,

Poznan, Poland, lies in the middle of Berlin and Warsaw. Having been to neither

city, we were attracted by Berlin’s magnetic historical and symbolic

significance, especially in regard to WWII and the Cold War. Most people know no

German, yet many know JFK’s famous words: “Ich bin ein Berliner!”

said in Berlin, during the early days of the Cold War.

The impact of Berlin’s significance begins with the airport we flew into, Tegel. During the Berlin Blockade, the existing airports in Berlin were not sufficient for the heavy air traffic. As a result, the French, unable to participate in the Air Lift in any meaningful way due to their preoccupation with the Franco-Indochina War, built a completely new airfield here, which subsequently morphed into the Tegel airport. It is noteworthy that while the French designed the airfield and oversaw the project, the actual work was carried out mostly by women of Berlin, as men were in short supply after WWII, and mostly by hand as heavy equipment was hard to ship to Berlin given the Soviet Blockade.

From Tegel, we took a bus to Alexanderplatz, where we stored our luggage in a locker, and started our hop on/hop off bus tour of the city. Then, in the afternoon, after a nap to overcome the jetlag, we took the first half of Rick Steves’ Berlin Audio Tour. Unfortunately by then we ran out of time and energy, and didn’t get to the second half.

Our first

hop-off stop was the Brandenburg Gate. It was in the no-man’s

land during the Cold War, and as such the most salient icon of the partition of

Berlin, and of the division of the world’s political ideologies. It was the

location for Ronald Reagan’s

resounding appeal “Mr. Gorbachev, Tear Down This Wall!”

Across the street, on the iron fence of “the Greater Tier Garden” near where The Wall used to stand, a private memorial commemorates those killed for trying to climb over the wall, all of them from the east side. While, knowing what we know, we had no difficulty imagining a government use a wall and bullets to keep its people from leaving its state borders, visiting that memorial was still a most sobering experience. There is no “Wall”, only a line of stone in the street to mark where the wall used to stand. Were it not for Rick Steves, we would have missed it.

We stayed in an

apartment not far from Check Point Charlie, a crossing point between the

American Sector and the Soviet Sector. The simple wooden guardhouse still stood

there, as well as the sign warning people that by passing under it, they were

leaving the American Sector. Today, there is an ‘acting’ guard there, prepared

to put the hats of American, British, French, or Soviet soldiers on any visitor.

This touristic contrivance trivializes history. We’d much prefer a statue of an

American soldier in its place. A couple of blocks to the east of Check Point

Charlie is the “Topography of Terror”, an exhibition of Nazi terror located

where Gestapo’s headquarter used to be. Jackson went there alone one evening to

see the remaining section of Berlin Wall, something we saw on the bus during

our HOHO tour. The wall was topped with a thick steel pipe to prevent people

from deploying hooks to aid their escape. Under twilight, he was able to see the

wall from both sides, imagining the fear of someone trying frantically to

climb over, knowing full well that there were weapons searching for him.

We chose Berlin as our transit to Poznan for its history. But we found more than what we were looking for. We were impressed by its present, and in particular, by its courage and conscience.

A short block

away on the north side of Brandenburg Gate is the Reichstag building, one chamber of the German

parliament. Rick Steves’ audio tour brought to our attention a memorial by the

entrance to the secured area of the Reichstag building, where a series of stone

slates memorialized parliament members murdered by the Nazis. Carved in the

stone are the name, date of the murder and party affiliation of each of the

victims. About equal distance away on the south side of Brandenburg Gate is the

Holocaust Memorial, a sea of coffin-like stone blocks that occupy an entire

street block. At a distance, the memorial looks like a labyrinth, with no clear

entry or exist point but a convoluted path of meaning to be experienced. To

dedicate such a large space so central to its capital to reexamine and reflect

upon the darkness and evil in its own history (rather than hiding, denying and

erasing them from the national memory) is itself a heartening achievement by

Germany, which sets a fine example for other nations.

A short block

away on the north side of Brandenburg Gate is the Reichstag building, one chamber of the German

parliament. Rick Steves’ audio tour brought to our attention a memorial by the

entrance to the secured area of the Reichstag building, where a series of stone

slates memorialized parliament members murdered by the Nazis. Carved in the

stone are the name, date of the murder and party affiliation of each of the

victims. About equal distance away on the south side of Brandenburg Gate is the

Holocaust Memorial, a sea of coffin-like stone blocks that occupy an entire

street block. At a distance, the memorial looks like a labyrinth, with no clear

entry or exist point but a convoluted path of meaning to be experienced. To

dedicate such a large space so central to its capital to reexamine and reflect

upon the darkness and evil in its own history (rather than hiding, denying and

erasing them from the national memory) is itself a heartening achievement by

Germany, which sets a fine example for other nations.

Not far from the Holocaust memorial is the location of Hitler’s final bunker, now filled in with dirt and intentionally left as an unpaved patch of parking lot. Only a plaque marks its location, and explains its historical significance. The destruction of the bunker was intentional, as the country did not want to leave a potential location for people to commemorate the Nazi leader.

Potsdam is at

the outer reaches of greater Berlin. Most people visiting Berlin for the first

time don’t go to Potsdam, and those who do visit Potsdam tend to go see the

grand palaces, especially the Sanssouci Palace and the New Palace, both rather

close to the main train station (Hauptbahnhof). Generally,

we are more enchanted by places that have shaped history than places with

spectacular appearances. So we chose as our primary destination Cecilienhof, a

minor palace pretty far from Potsdam city center. To get there, we walked, took

an U-Bahn, an S-Bahn, a tram, and a bus. But the trouble and the nearly two hours of travel were well

rewarded.

Cecilienhof is the location for the 1945 Potsdam Conference. Attending the conference were USSR leader Joseph Stalin, UK Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and US President Harry Truman. Five months prior to the Potsdam Conference, when the “big three” met in Yalta, the US was represented by Franklin D. Roosevelt. And during the Potsdam Conference, Churchill was replaced by Clement Atlee, the new Prime Minister of UK. Yet through all the changes of the cast, the policies of US and UK were largely continuous.

We saw the

conference room as it was laid out during the Potsdam Conference. The three

flags on the table indicate the seating arrangement of the three leaders. It was

here that Germany was partitioned. The American, British, and French zones

eventually became the West Germany, including a geographically separated West

Berlin, while the Soviet zone became the East Germany. It

was also during this conference Poland was

reconstituted and reshaped, gaining some land from Germany and losing some more to

the Soviet Union. A long documentary video (45 minutes?) that is played

alternatively in Polish and English in Cecilienhof gives a thorough account of

the historical circumstances and ramifications of the conference.

We saw the

conference room as it was laid out during the Potsdam Conference. The three

flags on the table indicate the seating arrangement of the three leaders. It was

here that Germany was partitioned. The American, British, and French zones

eventually became the West Germany, including a geographically separated West

Berlin, while the Soviet zone became the East Germany. It

was also during this conference Poland was

reconstituted and reshaped, gaining some land from Germany and losing some more to

the Soviet Union. A long documentary video (45 minutes?) that is played

alternatively in Polish and English in Cecilienhof gives a thorough account of

the historical circumstances and ramifications of the conference.

What piqued our particular interest in Potsdam Conference is the Potsdam Declaration. Truman, Churchill, and Chiang Kai-shek, who never participated in the Potsdam Conference, jointly declared the terms for Japanese unconditional surrender, with the alternative of “prompt and utter destruction”. As it was during the conference that Truman learned of the successful test of atomic bomb in New Mexico, the wording “prompt and utter destruction” could be parsed as a veiled threat of atomic bombs. Interestingly, the Potsdam Declaration was issued in the names of “We—the President of the United States, the President of the National Government of the Republic of China, and the Prime Minister of Great Britain”, on July 26, 1945, precisely the day Clement Atlee became the new Prime Minister of Great Britain. So reports of who issued the Potsdam Declaration on the UK part vary. We can find photos (and at least one YouTube video) of Potsdam Declaration with the signatures of Truman, Churchill, and Chiang Kai-shek, which, if authentic, means that Churchill must have signed the document ahead of the date, and Chiang Kai-shek afterwards.

From Cecilienhof, we walked back to the main train station of Potsdam, seeing many interesting sites on the way, guided by the Potsdam city audio tour. In the end, we ran out of energy, but not time, and must forego all the other palaces in Potsdam till our next visit.

*****

Let us conclude our travelogue of Poland and Germany with a quote from the founder of modern anthropology, Bronislaw Malinowski, who, we found out after the trip, was a native of Krakow!

…our final goal is to enrich and deepen our own world’s vision, to understand our own nature and to make it finer, intellectually and artistically. In grasping the essential outlook of others, with the reverence and real understanding, … we cannot but help widening our own.